No products

Manufacturers

Categories

- AK-47 Pattern Rifles

- AR-15 Accessories

- Beretta Accessories

- Canik Accessories

- CZ Accessories

- CZ P-07 & Duty

- CZ P-09

- CZ P-10 Series

- CZ Shadow 1

- CZ Shadow 2

- CZ Shadow 2 Compact

- P-01 / Compact

- P-01 Omega

- CZ 75 B

- CZ 85

- CZ 75 Tactical Sport

- CZ Scorpion

- Older CZ 75 (Pre-B)

- CZ 97 B

- CZ Branded Items

- Glock Accessories

- GLOCK Gen 1 - 3

- Holsters (Glock)

- Magazine Pouches (Glock)

- Competition rigs (Glock)

- Magazines (Glock)

- Performance Parts (Gen 3)

- Sights (Glock)

- Optic Mounts (Glock Gen 3)

- Lights / lasers (Glock)

- Spare Parts (Gen 3)

- Tools (Glock)

- Carbine Conversions (Gen 3)

- Grip Enhancements (Glock)

- Magazine Wells (Gen 3)

- Magazine Bases (Gen 3)

- GLOCK Gen 4

- Holsters (Glock)

- Magazine Pouches (Glock)

- Competition rigs (Glock)

- Sights (Gen4)

- Optic Mounts (Glock)

- Lights / lasers (Glock)

- Performance Parts (Glock Gen 4)

- Magazine Wells (Gen 4)

- Magazines (Glock)

- Magazine Bases (Gen 4)

- Tools (Glock)

- Spare parts (Glock Gen 4)

- Grip Enhancements (Glock)

- Carbine Conversions (Glock)

- GLOCK Gen 5

- Glock Slimline

- Holsters (Glock Slimline)

- Magazine Pouches (Glock Slimline)

- Magazines (Glock Slimline)

- Magazine Bases (Slimline)

- Performance Parts (Glock Slimline)

- Sights (Glock Slimline)

- Lights / lasers (Glock Slimline)

- Tools (Glock)

- Grip Enhancements (Glock Slimline)

- Optic Mounts (Slimline)

- Spare parts (Glock Slimline)

- Glock Branded Items

- GLOCK Gen 1 - 3

- Sig Sauer Accessories

- Smith & Wesson Accessories

- Vektor Accessories

- Long guns (rifle / shotgun)

- Lights and Lasers

- Gun Belts

- Gun Slings

- Training Aids

- Range Time

- Gun Care

- Reloading

- Miscellaneous

- Featured Products

- Tools

- End of line specials.

- Optical Sights

- 1911 Accessories

Sight Basics

“Most experts recommend tritium sights on a self-defense firearm. They glow permanently, allowing you to see your sights any time of the day or night.” If I have given this advice to one client, I have given it to a thousand. It is worth mentioning, though, that I’m not carrying tritium myself. I am not completely alone, as I’m seeing some top class shooters do the same. In this post, I’ll discuss the technology behind the two types of sights, and why you may choose one over the other.

Sight technology

Let’s start with plain, unmarked sights. These are designed to absorb as much light as possible, etching a perfectly black silhouette against a bright background (think paper target). If the target itself doesn’t reflect a lot of light, though (think dark clothing or bad light), we lose a lot of contrast, making the sights difficult to pick up. Adding some white highlights to the sights give us a sight picture that is less dependant on the background, making for a good all-round sight. This is why most duty pistols come out of the box with white highlights. We can go a whole lot better, though, if we choose our sights depending on our specific need.

Our brains are well developed to pick up bright colours against the more subdued colours of nature. Unlike white objects, though, which reflect all visible wavelengths, coloured objects reflect only their specific wavelength light, leaving us with much less contrast when things get darker. On top of that, the more light-sensitive rods that our eyes use for low light, can't distinguish colour. This explains why red or green is easiest to pick up during bright light, but yellow is better at dusk and white when it is really dark.

So far, I have discussed normal paint only. Since these simply reflect the available light, it loses most of its value as darkness sets. Photoluminescent paint, on the other hand, has the ability to absorb light and release it over time. In theory, these should make the sights useable in all lighting conditions, but the reality is that most of our pistols live in the dark (holster or safe) so we can’t rely on the sights to be ‘charged’ when we need them the most. The ideal night sight would therefor generate its own light to glow permanently. This is where tritium sights shine. They emit light permanently, so we know they will be visible whenever we need them.

The ideal day sight, on the other hand, would make use of the abundance of available light. This is best achieved by installing a length of fiber optic rod in the sight. The fiber optic rod collects light along its entire length and emits it only through the open ends. This creates a very bright highlight that makes the sight easier to track on its way to the target, or through recoil. It should be mentioned that the fibers themselves don’t aid accuracy as much as it does speed. Accuracy is best achieved by aiming with the steel edges of the sight. High-quality fiber sights are usually precision manufactured and incorporate other design details, such as serrations, that do support accuracy, though.

Lighting conditions

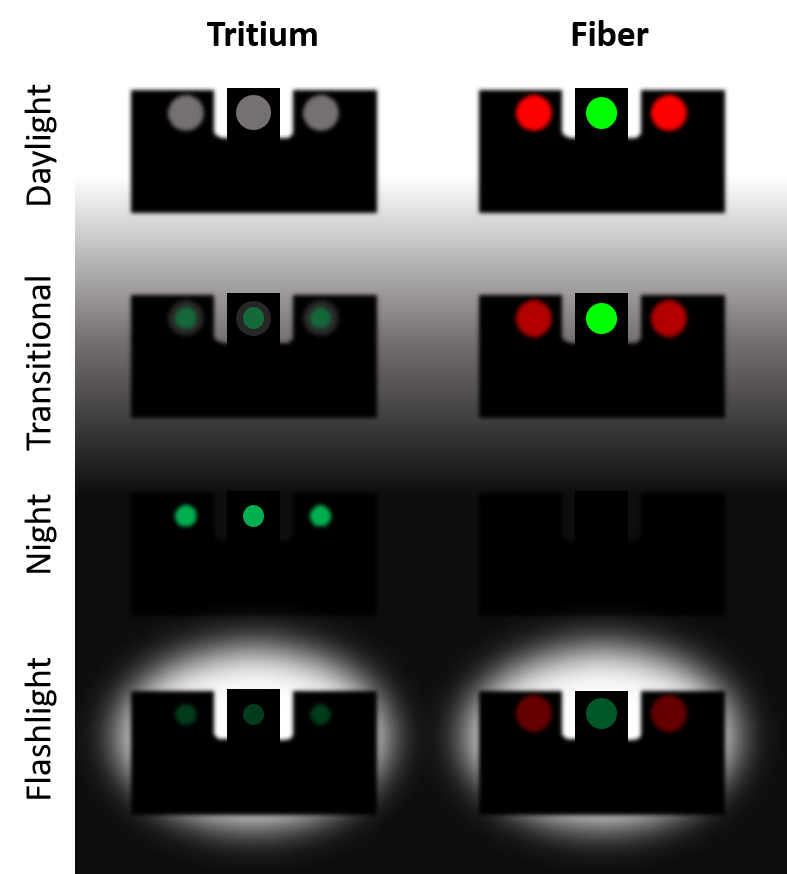

In the image below, I try to depict what my eyes see when I look at tritium and fiber sights in different lighting conditions. I can only speak for myself because of, well, let’s call it calibration issues. I don’t know what your eyes are like, but I do know that I’m struggling more to distinguish contrast as I’m getting older, so I can believe that yours might be different than mine.

The top two sights in the picture illustrate tritium and fiber sights in bright daylight. Fibers are obviously a lot more visible than tritium. The grey dots on the tritium sights in the image represent the lenses over the tritium vials that reflect some light to create brightish spots. The green glow of the tritium itself is not visible at all. The third set of sights represent what you can expect to see in pitch darkness, the tritium is very visible while fiber sights disappear altogether. So far, nothing new. The interesting part is what I see in other lighting conditions.

According to the internet, tritium sights are very good for transitional lighting conditions like dusk or dawn. Not for my eyes, though. As the transitional light pictures show, I can’t see the tritium glowing unless I really try , and I can’t see the silhouette of the steel unless I really try, slowing me right down. On the other hand, as the light becomes less and my pupils dilute, the fiber sights seem to grow brighter and brighter. As the light continues to dim, fibers start to lose prominence again until they disappear completely.

Adding a flashlight, whether handheld or weapon mounted, changes the picture again. Gone are most of the tritium glow, and I’m back to relying on the silhouette. Some light does enter the fibers from the muzzle side, but basically everything is dominated by the silhouette of the sights against the bright spot of the flashlight.

There are other variables at play, too. An attacker with very dark clothing might cause problems even in broad daylight, while a fortunate light source might spill onto your fibers at night. For example, I’m perfectly happy to dry-fire practice at night with my fiber sights, as long as I’m fairly close to a ceiling light. At the other end of the spectrum, I remember struggling so long to find my tritium sights in a daylight match that I reverted to simply aiming along the top of my slide. I was using my carry gun in an IDPA match, the target was wearing a navy blue t-shirt in the shade, and there just wasn’t enough contrast to work with.

Best-of-both

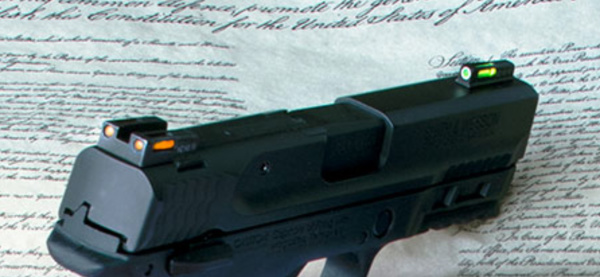

Sight designers have played with various configurations to try and get the best of both worlds. Some sights placed the fibers on top of the tritium dots for a tallish, Christmas tree type of sight. These never seemed to catch on, though. Placing tritium vials behind the fiber rods seem to be more popular these days. These give you the best of both worlds, although they do tend to be slightly less bright than single-purpose sights, and considerably more expensive. Another popular solution is adding a brightly coloured ring around the front fiber for daytime visibility. These rings are usually photoluminescent as well, adding the promise of some extra glow at night, but I don’t think most owners even realise this.

Understanding the threat

When it comes to self-defense, we are the hunted, not the hunters. We don’t get to choose the conditions, our attackers do, but we do know that they like the dark. This is why tritium sights are the default recommendation. They are always somewhat visible. But somewhat visible may not be good enough if the window of opportunity is very small.

Any self-defense scenario will be a extremely busy time. You will have to make one of the most important decisions of your (and somebody else’s) life and execute that decision fast and efficiently. You may need to shoot on the move. Your target may move, and innocent people in the background may move. You will probably be behind the curve to start off with. If there are two attackers, Number Two will have a massive time advantage while you are focusing on Number One. In situations like these, you will need any advantage that you can get.

Just as you may find yourself in need of extreme accuracy without enough sights, you may find ourself in need of extreme speed without enough sights. It is easy to understand the first scenario – if you have ever picked up your pistol in the dark, and couldn’t see anything, then you can do the math. It is more difficult to understand the probability forest of the second scenario, though. We don’t know how much time we’ll have before the final bullet comes our way, and we don’t know how much time a high visibility sight will save us. Most importantly, we don’t know how to reduce all these uncertainties into a single recommendation. (Basing our decision only on the scenario with the best available information is a common error, named availability bias.) There may be a couple of operator types in the world with enough experience to add numbers to those probabilities, and a couple of academic types with enough knowledge to build those numbers into a proper decision-making model, but I don’t think those guys hang around the same watering holes. My approach to this (and similar decisions), is to start with the default recommendation. In this case: tritium. From there I decide if my considerations are more or less the same of the people making that recommendation, or if it leans sufficiently to one side to warrant a different approach.

Lastly, keep in mind that you need to know what you are shooting at. So whether your sights need it or not, you need light on the subject before engaging.

Final considerations

I am a strong proponent of a pistol that shoots exactly where it is aimed, which is why I have adjustable sights on my sporting pistol. To be honest, though, this is driven more by a search for the best possible feedback when practising than by the need for absolute accuracy when taking part in a competition. I am therefore quite comfortable to prioritise other aspects on my carry gun. Apart from that, adjustable sights tend to be bulkier, have sharp corners and be less robust than fixed sights. Little wonder then that fixed rear sights dominate the self defense market.

In fact, robustness is an important consideration for carry sights. Some sights even have built-in ledges that allow you to rack the slide on any surface for one-handed manipulation. Fiber sights do tend to be a bit more fragile, andI have seen some of them break. So if you are serious about robustness, I would not advise against fiber sights, but I would recommend choosing a compact, sturdy design.

Sport shooters often prefer rear sights to be as plain as possible, so as not to distract from the front sight, which is where your attention should be focused. We are finding that sight sets with highlights on both front and rear sights are still dominating the self-defense market, from both a supply and demand perspective.

Hunters know the importance of having a suitable telescope on their rifles, and they accept that it will cost a significant part of the overall package. Knowing where the hole will end up is equally important on a handgun, but because the fixed sights seem so much less complex than a telescopic sight, we sometimes need to be reminded about the technology that goes into them before we are willing to part with our money. Tritium is a radioactive hydrogen isotope. Hydrogen is a gas, so it has to be contained in glass vials. The vials are usually protected by additional aluminium tubes along their length, and hardened glass at the front - all of that in a tiny little package. Three of them, actually. So not only are tritium sights quite expensive to make, but they can be quite problematic to move across borders.

Conclusion

The default recommendation stands: Fibers for sporting guns, tritium for defensive guns. Keep in mind, though, that any self-defense scenario will be the competition of your lifetime.